I meant to post this a few days ago but unexpectedly found myself away on assignment. It’s short video clip showing my favourite pictures on the Reuters wire in 2018.

I meant to post this a few days ago but unexpectedly found myself away on assignment. It’s short video clip showing my favourite pictures on the Reuters wire in 2018.

October 16, 2017

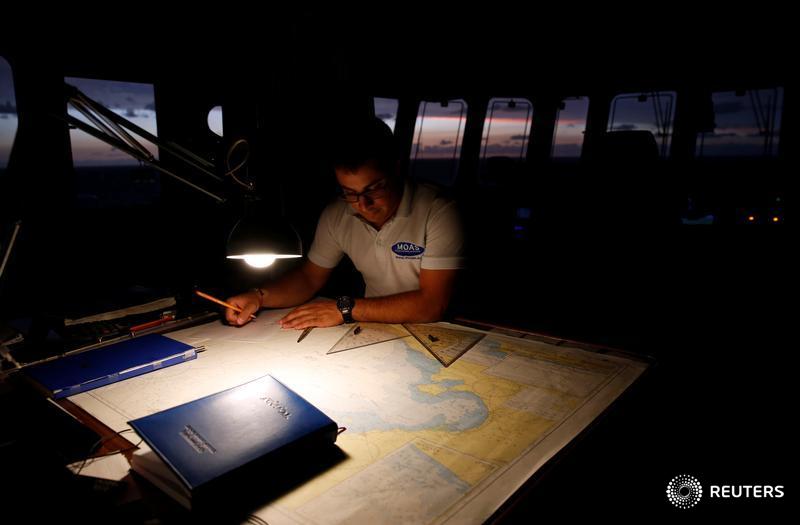

It was just another quiet day, taking things easy and getting some rest, having returned home only a few days earlier from a fortnight-long assignment out at sea on a migrant search and rescue mission.

I picked up my daughter from school at 3pm, and was back home some 10 minutes later. My computer was on, and as I often did, I had a look at Daphne’s Running Commentary blog to see what the latest was on anything concerning government corruption and the like. Just over half an hour earlier, she posted a piece about the prime ministers chief of staff going to court to argue he’s not a crook. My wife prepared some lunch for Becs, I probably had something to eat as well. We sat down in front of the TV to watch an episode of Doctor Who on the Blu-Ray player. We must have been about half way through the episode when my phone rang. I saw it was my mother. I answered it, and heard her panicking voice -“Have you heard? They blew up Daphne, they killed her!” I thought I was hearing things, I probably asked her to repeat that. I don’t know precisely what I did next, but must have stopped the blu-ray, switched to TV news, and sure enough, saw an flash news broadcast with the news headline saying there had been a car bomb explosion and that the victim was believed to be Daphne Caruana Galizia, a fearless anti-corruption journalist, my first direct superior when I first starting working in newspapers, my friend, my cousin. I dashed into my study, made sure I had all the right photo gear on me in my kit bag, and got out of the house, a mix of shock, horror, confusion sweeping over me. I texted my regional chief in Paris to alert him, and then got in the car and started driving, saying to myself over and over, it’s not true, someone got this wrong but stay calm and concentrate on driving. Along the way, I pulled over to check online news websites, both to see if there were more details and also to double check where the explosion took place. Yes, it was Bidnija, the little village where she lived.

I think by the time I reached the location and was driving through the first police roadblock after showing my press credentials, I knew it was her, being on the road that leads to her house.

I parked behind a row cars which I recognised as belonging to other press members, and walked the last bit. I could see them gathered behind police tape some fifty meters up the road. Whilst walking I called Mal in Paris, who hadn’t responded to my text message. He answered right away, hadn’t seen the message as he was driving. I quickly explained what I knew so far, and told him Daphne was my cousin. He was shocked, and immediately offered any help I might need. I told him all I needed for now was someone to wait for and edit and distribute my images. He sorted that right away and within a couple of minutes, I had an email from an editor in Paris saying he was standing by waiting for the first pictures to land as I filed images straight off the back of my cameras.

I couldn’t see much from that angle, all the police, army and medical vehicles were blocking the view. I shot a few frames, quickly returned to the car to get a bigger lens, went back up and shot what I could, then filed them straight off the camera and called the editor to let him know I’d sent him the pix, as well as to give him some basic information on what was happening and the location.

A former colleague mentioned that it was possible to see the destroyed car from the other side of the valley. I quickly worked out in my mind the quickest route to get there, got it hopelessly wrong, but eventually reached the spot from where we had a better view of what was happening. The burnt-out remains of the car were in the middle of a field. I was trying to work fast, didn’t mention to anyone at first that Daphne and I were related.

I was shooting and filing as fast as I could, and also thinking about whether we could somehow get closer. Could we get into this villa under construction next to us perhaps? Someone had already tried and the police threatened to arrest him for trespassing.

Everyone was in shock. Many of the press people here didn’t like her at all, but that didn’t detract from their shock and horror.

I wasn’t processing this. I was just thinking of getting the pix out and monitoring the Reuters news pictures feed through my mobile. Then I mentioned to one of the photographers that she was a cousin. He was stunned, said he was really sorry, and then the others did too, and I think that was when it hit me. This was Daphne, my friend, my cousin and a damn fine journalist to boot, the best of her kind, and she was dead. I needed to sit down for a couple of minutes. I needed to rest for a moment, and I felt I needed to react to what happened, somehow, anyhow. I wanted to cry for a minute, but I couldn’t. So I got on with the work, waiting for police officers to walk into the picture and the like. As it was getting dark, I remembered I had portraits of Daphne (shot in 2011) stored in my online archive, so I accessed them and sent those to the editor in Paris as well.

It was soon dark, but activity continued on the bombing site. The police had set up some floodlights in the area, which also enabled us to continue to shoot. I took some pictures of forensic investigators, who then started making their way up the road towards us. They told us we’d have to move further back, as they needed to secure the area that we were in too.

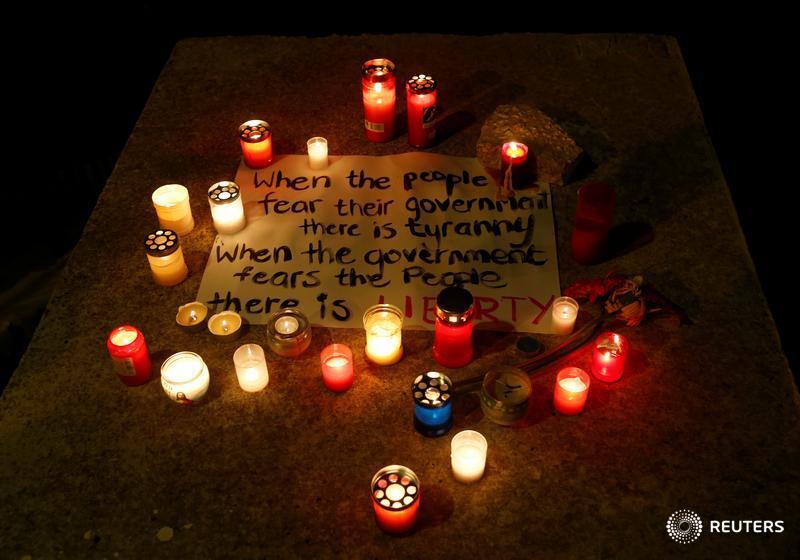

I felt I had enough pictures, and wanted to get to the vigil being organized, about which word was rapidly being spread on social media. I can’t remember if I popped home before going to the march/vigil. I found it very hard to park in Sliema, the town in which both Daphne and I were brought up. I took that to be a good sign – it meant lots of people must be turning up for the silent walk. I ended up in an expensive car park beneath a hotel, and walked a considerable distance to where the vigil was supposed to take place. I got there, bumped into a close friend who happened to be in Malta for a few days, and she told me that people had started walking ages ago. There were so many people, that the ones on this end hadn’t even yet been able to start walking along the promenade. As I tried to make my way towards the front of the march, I recognised so many faces, all drawn, solemn, shocked, stunned. No anger, it was too soon for that.

Occasionally I would pause to shoot some pictures, and tourists, seeing me with cameras and deducing that I would know what was going on, would come up to me to ask what happened. All appeared shocked when I told them our top investigative journalist had just been blown up in a car bomb explosion.

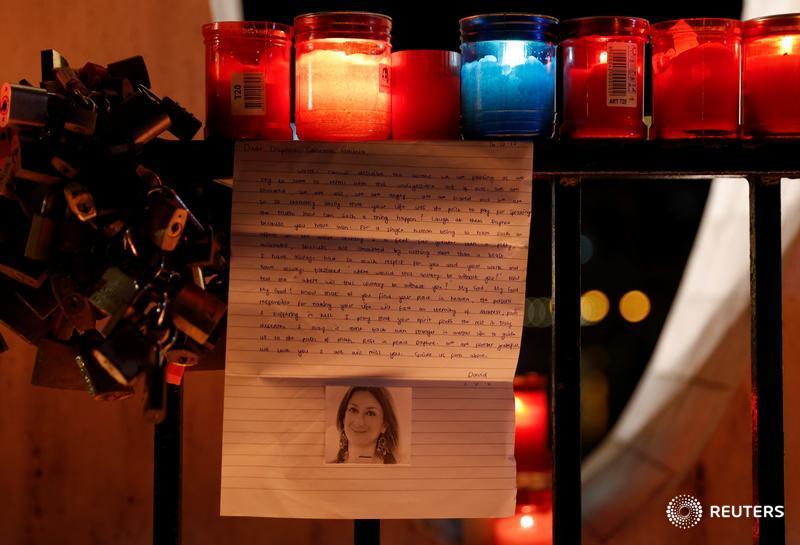

When I got to the Love monument at the end of the promenade, where the walk was meant to end, people were already laying hundreds of candles. The monument was being turned into a memorial. I remembered I’d been in this very spot the day before, under very different circumstances, photographing the start of a Doctor Klown parade, supposedly the largest-ever gathering of clowns in Malta, which was a walk in the opposite direction, towards the starting point of this one. It felt surreal.

I wished I had a candle to light and place too, but I didn’t. So I just concentrated on making pictures. I knew I would have to edit and file these myself, but I didn’t want to rush to get them out. I decided I was going to take my time, knowing that the important images for tomorrow’s papers worldwide had already landed on clients’ desks.

I met many friends, other cousins – we were all stunned, there really wasn’t much anyone could say to anybody.

I stayed long at the memorial. By the time I decided to leave, most people had already gone. I was now a good 45 minutes brisk walk away from my car, and started to make my way back slowly. Then I remembered I wasn’t done. I had to edit and file some pictures. So I sat down on a bench and did that. Doing so also gave me the chance to breathe and rest for a while. I hadn’t realised up till this point that I was physically exhausted. Emotionally and mentally, hard to tell. I still wasn’t processing things in my mind. I was too stunned and at the same time trying to stick to working on autopilot.

Pictures filed (I also dug up another file photo of Daphne I remembered I had), I continued walking along the promenade back to my car. Being exhausted, I sat down again.

I sat there for quite a while, I really must have been knackered. It was around 1am when two people walking by stopped and called my name. It was hard to recognise who it was, being silhouetted against a street lamp. Then I realised it was one of Daphne’s sisters with her husband.

What could we say to each other? Just hold each other tight, very tight, for what seemed like forever, as she sobbed. All I could do is say “I’m so sorry, so sorry”. They were coming from her parents. I asked how they were – stupid question but one has to ask.

I told them what I’d seen during the vigil, the thousands of people who’d turned up, and suggested they should pass by the memorial on their way to their car which was parked in its vicinity. They said they would.

I think we stayed there together for half an hour or so. Once they moved on, I carried on towards my car, and once there, decided I’d drive home via the memorial, just to have another look. When I drove by, Daphne’s sister and her husband were there, reading some of the messages left. I didn’t stop, I just drove by slowly and then carried on home. I didn’t sleep well that night, is it any surprise?

A lot has happened since then – I’ve been privileged to be part of the Daphne Project, working closely with other team members in their investigations into who commissioned the murder and continuing Daphne’s investigations. I’ve travelled extensively over the last twelve months, on unrelated matters, but without exception, I’m always asked about this case. I’ve covered the story relentlessly and intend to continue doing so. Yet sometimes, a sense of despair does take hold as I question whether we’ll ever find out who was behind this heinous act. Then I remember that Daphne herself would have never stopped, and so, neither must I, neither must any of us who are on the side of what is right.

Twenty years ago today I had my first picture used on the Reuters wire, the start of an incredible experience that carries on right till the present and hopefully many years into the future. It’s been a terrific buzz, with so many people who’ve guided and mentored me over the years – David Viggers, Steve Crisp, Nigel Small, Dylan Martinez, Chris Helgren, Mal Langsdon, Catherine Benson, Simon Newman, Alexia Singh, Gabrielle Fonseca Johnson, Russell Boyce, Reinhard Krause, Rickey Rogers, Corinne Perkins, Pawel Kopczynski, Tom Szlukoveny, and so many others. Eternally grateful to each and every one of you. And a special thanks to Paul Delmar, who one fine day in 1997 thought he’d set up a meeting for me with David Viggers and Steve Crisp at Gray’s Inn Road. Together with my girlfriend Adriana, I dashed down to London from Sheffield that same evening in order to make it to the meeting the following morning. Thinking I wouldn’t be long in the meeting, Adriana and I agreed she’d wait for me downstairs in the lobby. I got so absorbed in things that I forgot about her waiting there, and she sat patiently for three hours before heading off to a nearby museum! (we had no mobile phones back then).

That first picture on the wire showed traffic control police waiting for a convoy of heavy vehicles driven by striking Malta Freeport cargo haulers heading towards the Maltese capital Valletta on December 9, 1997. Later that evening, once the image popped up on the wire at the Times of Malta newsroom, my late-colleague Alfred Giglio snapped a corny thumbs-up pic of me celebrating.

As a very eventful year draws to a close, I’ve put together a loosely edited gallery of some of my favourite images shot in 2016. It’s by no means exhaustive, nor fully representative of all the stuff I’ve shot over these last twelve months. I hope you enjoy them.

A good friend passed away today. Lino Arrigo Azzopardi, an Associated Press photographer here in Malta for many years, passed away aged 77 after a battle with cancer, a battle which destroyed his health and his body, but not his sense of humour and his joyful, funny character traits. He was one of a kind, a chap I learnt so much from, particularly in my early days as an upcoming wire photographer. Though we worked for competing agencies, that never got in the way of helping each other out – sometimes it might have been helping with equipment technical issues, or passing on a few image negatives when one of us missed an event, or tip-offs.

Lino and I at the Office of the Prime Minister in 1998, waiting for the newly-elected prime minister to arrive after winning the general elections.

He’d cheated death before, having had a narrow escape in a traffic accident while he was travelling in the Maltese President’s motorcade in Bulgaria in 2001. Recovery and recuperation took several months. He had been working as the President’s and Prime Minister’s official photographer on overseas visits for several years – once he was out of action, he recommended that I take his place until he was well again, a gesture that enabled me to travel to some wonderful and distant parts of the globe.

Fond memories are too many to write here. But the ones which most comes to mind, something we’d often reminisce about whenever we met and have a bellyful of laughs about, was when Britain’s Queen Elizabeth visited Malta for a day in 2007 – we were on the same fixed photo position, both armed with long lenses, waiting for the Queen to walk out of a public garden and come towards us. Hundreds of people lined the barriers along the side, waiting to catch a glimpse of the Queen. As she approached, our view of her was totally obstructed by members of her entourage, protection detail and roving photographers and TV cameramen. Both Lino and I started shouting and yelling for them to get out of the way. I’m sure there was the odd bit of blasphemy thrown in as well. People, including many tourists, were horrified – they thought we were shouting and swearing at the Queen herself.

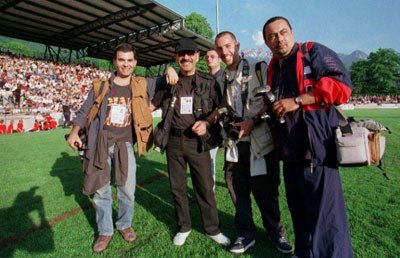

Myself, Paul Zammit Cordina, Lino and Stephen Gatt before the Malta vs Italy Euro 2016 qualifier

Another fond memory goes back to the day we were working on the MV Arctic Sea story in 2009. The Maltese-registered freighter had just been handed back to its Finnish owners by Russia, just outside Maltese territorial waters, more than two months after its forces recovered it off the Cape Verde Islands. Arctic Sea had disappeared in the Atlantic after being boarded by eight hijackers in the Baltic Sea in July, causing a media storm. When the ship had anchored just outside Maltese waters, a few days before it was eventually towed into harbour, Lino and I had got on a friend’s boat and spent the whole day at sea, checking out as many ships as we could in the limited charter time we had, trying to (unsuccessfully) get some pictures of the freighter.

Lino covers the arrival of evacuees from Libya in 2011

Perhaps one of the funniest memories goes back to 1999. We were covering the Games of the Small States of Europe in Liechtenstein. Our hotel was across the border in a small Austrian town, the name of which escapes me at the moment. On our first evening there, our group of around half a dozen or so journalists walked around the town for ages, looking for a place to have dinner. It was late, most places were closed. Eventually, we found one restaurant which seemed to be about to close, but the owner waved us in. As we sat inside, Lino was trying to communicate with the owner in very broken German, getting quite frustrated when they weren’t managing to understand each other. It took a good half an hour before someone twigged onto the fact that the restaurant owner was Italian, and all of us were fluent Italian speakers.

Myself, Lino, Matthew Mirabelli and Charles Marsh at the Games of the Small States of Europe in Liechtenstein, 1999

I could go on and on …. so many memories, but I’ll leave it at that. So long Lino, you were larger than life. As they say, till we meet again, old friend.

I’ve been a staff photographer with the Times of Malta, the largest national newspaper on the Maltese Islands, for over 20 years. Over all this time, I’ve had some pretty memorable and exciting experiences, and have so many memories I truly cherish that it’s impossible to count them all. I’ve met interesting people from all walks of life in several countries, witnessed history in the making, been privileged and touched to get deeply involved while working on human stories and also done my fair share of what can only be described as very mundane coverages, all of which are part and parcel of any press photographer’s life.

Yet, some time ago I felt the overwhelming urge to move on. Maybe I’d grown tired and felt my work was beginning to go a bit stale. I craved new challenges, so just under three months ago, I handed in my notice at the paper at which I’d spent close to half my life.

I decided I’d freelance from now onwards, while concentrating more on the work I do for Reuters as well as my own projects. I’ve been a contractor with the agency since 1997, and wanted to increase my input and involvement with it. Meanwhile, I’ll continue doing some work for the Times of Malta, but this time in a freelance capacity.

Today was my first post-Times of Malta day, officially a freelancer, something I hadn’t been since 1996. I’d planned a quiet day, having decided to take a few days’ break till I get going again – do a spot of Christmas shopping, take my daughter to a movie, go for a long walk with the dog.

All that changed as soon as I bought my cinema tickets online. I got a call from someone informing me that a hijacked plane was about to land in Malta. With plans instantly flung out of the window, I picked up my gear, quickly made sure that everything I might possibly need for this sort of assignment was in place (things such as lens extenders, spare battery packs, Mi-Fi units, wireless transmitter for the camera, as well as the usual basics), together with some warm clothing, jumped into the car and dashed towards the airport, heading for the spot where I knew a hijacked plane would be sent to.

I called my Reuters boss in Paris to alert him about the developing situation from the car (yes, using a hands free set of course 🙂 Traffic was light, I got there in no time at all. The police had already blocked off access roads but waved me through when I flashed my press card at them. I was stopped by other officers further in, and told to walk the rest of the way, which was fine. I was less than a hundred metres from the spot I wanted to shoot from. It wasn’t ideal lighting-wise as I would be shooting against the light, but it allowed for good images of soldiers in front of the hijacked aircraft.

The plane had been on the ground for about twenty minutes. The important thing in these sort of situations is speed. Getting the first few pictures out on the wire as quickly as possible is paramount. I shot a few frames, starting wide to get the whole plane in, and then switching to a longer lens with an extender to shoot tighter images. Using the wireless transmitter on the camera and a Mi-fi unit, I was able to send some pictures straight to an editor in Paris, who quickly editing, captioned and sent them out on the wire from which they could be retrieved by a network of thousands of clients worldwide. That capability is essential for any wire services photographer – it enables the photographer to concentrate on taking pictures instead of having to stop shooting, switch on a laptop, download and then select and file pictures. I also shot some video clips on my DSLR for our TV clients, as my Reuters TV colleague hadn’t reached the location yet.

The traffic police officer who’d earlier waved me through the road block turned up on his bike, and said he’d made a mistake by allowing the media through, and that we’d have to pack up right away and leave, as we were too close (he claimed) for our own safety. Fair enough – the hijackers were threatening to blow up the plane, and if that did happen, we might have been taken out by flying shrapnel.

We stalled as long as we could – the national TV broadcaster team were doing a live link and they begged to be allowed to wrap it up instead of interrupting it. That gave us an extra five minutes on site.

As my images were being transmitted, I took a few calls from different news organisations, and quickly looked up some information on what was actually happening – The Afriqiyah Airways A320 with around 120 people on board had been hijacked in Libyan airspace. The plane was on an internal flight from Sebha to Tripoli when it was diverted by two hijackers, believed to be in their mid 20s, who were threatening to blow up the plane. A total of 111 passengers – 82 men, 28 women and an infant, all believed to be Libyan – and six crew members were on board the aircraft.

Once back in the car, I knew where I should head to. I’d once done a bit of a recce around the airport with just this sort of situation in mind. Once I got there and parked, I decided to carry all my gear and warm clothing with me. I knew that once I found a good spot to shoot from, I’d be unable to leave till the whole thing was over, both because I couldn’t risk missing some major development and because access might then be blocked and I’d be unable to return. I’ll worry about food and water later, I told myself, while hoping it would all be resolved quickly and wouldn’t drag on for two or three days.

I made my way down the country lane to where I figured I’d have a decent view of the plane. As soon as I got there, a police officer appeared and gave me and another photographer our marching orders. Trying to reason with him wasn’t going to get us anywhere – he had his orders and he wouldn’t budge. No worries, we’d walked past a couple of farmhouses on the way in – I was certain the owners would let us onto their roofs if we asked politely.

Within a couple of minutes, we were setting up on a rooftop. The angle was good, we were at a safe distance even if the plane did blow up, even if the picture below might make one think otherwise.

It wasn’t long before the same police officer came down the lane, ordering us to leave. Of course, I stood my ground. I know my rights in these sort of situations – I was on private property at the owner’s invitation. Even if there was a safety issue, I was under no obligation to comply with the order, even though he said it came from the highest level. What set alarm bells ringing in my head is he was only ordering the guys with the cameras to leave – he was quite content to leave the farmer and his buddies there. So someone somewhere simply didn’t want pictures and footage to be shot. He asked for my particulars which I shouted out to him from the rooftop, I took note of his service number, he got on his phone and walked away. He didn’t bother us again. Some soldiers tried something similar, but we ignored them too. They do this sort of thing sometimes – it intimidates less experienced journalists who might not be too sure of their rights so they think it’s worth a try.

I shot a couple more video clips, then quickly edited all the footage I’d shot so far, called the TV editor in Rome and transmitted the edited clip. Before long, it was playing on major TV networks worldwide.

One of the owner’s friends was listening to radio conversation between the pilot and the control tower so we had a pretty good idea of what was going on. We were able to ready ourselves for the first disembarking of released hostages – women and children first, as always.

One surreal fact was occurring to me. To the left, not far from the area where the military were stationed, was the film set of the movie “Entebbe“, dealing with the infamous 1976 hijacking of an Air France plane to Entebbe, Uganda, which resulted in the Israeli Defence Force mounting one of the most daring rescue missions of all time. Shooting on the film set wrapped a few days ago – though already being dismantled, one could still see signs reading “Uganda welcomes you.” But the Maltese soldiers were just a bit too far for it to make an interesting juxtaposition in a picture. (There’s further irony to the fact the film was being shot in Malta – the first movie about the hijack, which was made shortly after the actual event, was banned in Malta for several years for purely political reasons.)

Passengers were disembarking in pairs. Everyone seemed remarkably calm. You’d never have imagined they’d just been through a hijacking experience. Two female crew members were also released by the hijackers.

I managed to get some pictures of the disembarking passengers, but then lost the mobile internet signal. The farm owner told me is comes and goes in that area and was very unreliable. I was unable to get it back as the story unfolded to its conclusion.

The chap who was able to listen to the tower conversations decided it was time for him to leave, so we no longer had any information on what was going on onboard the aircraft. We just had to keep our eyes and lenses trained on it constantly. We had seen a couple of crew members come out of the plane onto the top of the staircase, but suddenly a man we hadn’t seen before appeared, waving a green flag. We knew all the passengers had disembarked, he wasn’t a crew member, and was waving what looked like a Gaddafi-era flag. Therefore, we quickly concluded the odds were he was one of the hijackers. So far, this was the money shot. I had the pictures, but frustratingly, repeated attempts to transmit the pictures kept failing because of the intermittent signal.

We saw military armoured vehicles on the move, approaching the aircraft. These were heavily armed special forces soldiers of the recently-set up Special Operations Unit. They drove out of our line-of-sight but it was clear that something was happening.

A few minutes later, the remaining crew members started descending from the airplane. One of them carried the same flag the hijacker had been waving earlier. The crew members moved off to the side, and the two hijackers came out, slowly and calmly walking down the steps. At the bottom, one went down on his knees. The other, the one we’d seen earlier, stepped forward, first put his pistol on the ground and then placed what looked like a document folder on the ground, and then dropped to his knees while holding his hands up. Soldiers crept into my field of vision, cautiously approaching the two terrorists.

The two must have been ordered to move apart from each other and turn away from the soldiers. One lay down on the ground, and soldiers swooped forward to restrain him while their colleagues kept their guns trained on the other.

The second hijacker was then approached, quickly restrained, searched and pulled to the ground. The four-hour standoff was over.

All that remained now was getting the images out to the world. The internet still wasn’t working. I had to make a judgement call. While I needed to get this pictures to the agency without further delay, I knew that if I left, I might (and in fact did) miss a good shot of the special forces soldiers embarking on the plane to conduct a full sweep of it. A quick phone call to Paris to discuss with my editor settled it. I would leave. I switched the cards in my cameras, just in case I came across another police officer who’d have decided to be funny with me. That was unnecessary as it turned out but it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Once I got to the car and drove off, it didn’t take long to find an area where I could get a good 4G signal, so I pulled over and filed the images.

Later it transpired that the hijackers’ weapons – pistols and a grenade- were harmless replicas. Luckily, all went well without a single shot being fired and no one getting hurt – a far cry from the last hijack to take place in Malta, during which some 60 hostages were killed when an assault on the Egyptair plane by Egyptian commandos went horribly wrong.

Definitely one to remember, as far as the first day on the job goes.

An edited version of this was published on Reuters Wider Image on July 4, 2016.

We spent the first six days at sea with nothing very much to do. The unstable weather, and the high swell, meant that boats were not departing from Libya. Of course, a 24-hour watch was still mounted on the Topaz Responder, a rescue ship of the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS), but no one really expected us to see any action for several days. Even when the sea was calm out where we were, the information we had was that on the coast, the swell remained high, making it dangerous for the smugglers to launch the migrants boats.

We’d pass the time with lots of chats with the crew, reading, watching movies, writing emails, following the Euro 2016 finals through a couple of apps on my phone, and most importantly, practicing various rescue drills, which I also found useful on a personal level, as it enabled me to familiarise myself with operating on the small FRDCs (Fast Rescue Daughter Craft) without smashing any camera gear, never a good idea at the best of times, let alone when you’re out at sea several days away from a camera repair centre!

Though I’d embedded with MOAS before, this was my first time on the Topaz Responder and her two FRDCs, named Alan and Galib in memory of Alan Kurdi and his brother Galib, the two Syrian boys whose deaths made global headlines after they drowned in September 2015 while attempting to cross from Turkey to the Greek island of Kos.

We also saw what I think is the most spectacular sunset I’ve ever seen. I set myself a personal project of photographing the texture of waves – Anything to kill time, really.

On the seventh day at sea, we finally got to do what we were out there to do. Save lives.

Every morning over the past week, I’d been waking up round dawn, at 5.30a.m., Usually only to be told that there weren’t reports of any sightings. So sometimes I’d head back into my bunk to catch up on some more sleep. Not this time round though. Over the next few hours, more and more reports would come in of more flimsy rubber dinghies packed with migrants kept coming in. From the Responder, we could count up to 21. By the end of the day, the final count, according to the Italian Coast Guard, was 42 boats carrying some 4,500 souls. Of those, one person was dead before rescuers could arrive – only one out of 4,500, but still one too many.

Several rescue ships took part in the operation – Italian coast guard and navy, British Royal Navy, MSF, Sea Watch. A Spanish SAR plane flew overhead.

Camera gear was all set to go – every night I’d ensure that everything was ready to be picked up and used at a moment’s notice. I suited up in my Tyvek coveralls, waterproof boots, life vest and helmet with a GoPro action camera mounted on top.

I got into the FRDC, together with its’ three man crew, two rescue swimmers, a medic, a MOAS cameraman and two huge sacks of lifejackets. We approached the closest dinghy and began throwing life jackets to its occupants. Once all the migrants had their life jackets on, the Topaz Responder drew closer, and the FRDC gently nudged the dinghy up against the ship so that the migrants could climb aboard.

That done, I returned to the Topaz Responder to photograph the goings on around the deck – the FRDC meanwhile moved away to distribute life jackets on more dinghies.

Once the second group arrived, I was able to see up close the sheer delight and palpable relief in people’s eyes once they were safely on board. Several dropped to their knees in prayers of thanksgiving, as they waited to be frisked by security personnel.

A collapsed migrant is assisted by Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) rescuers after boarding the MOAS ship Topaz Responder around 20 nautical miles off the coast of Libya, June 23, 2016. REUTERS/Darrin Zammit Lupi

By the time the third boat arrived, the deck was beginning to get crowded. People on this dinghy appeared more tense and fearful than the ones who’d been rescued earlier. They also had several babies with them, each one not more than a few months old. Babies were being passed to a rescuer, who would hand it to another crewmember. I was the closest and this was one of those times when, though you want to take the picture, if you need to help, then you drop the cameras by your side and help. I lifted a baby out of the arms of one of the rescuer who was sitting over the side of the ship over the dinghy and rushed it towards the medical centre outside which a nurse took the baby into his arms.

There seemed to be a greater sense of urgency. Lots of pushing among the migrants to try get off before others, desperate outstretched arms and hands trying to clasp the hand of a rescuer. Among the ones getting onto the ship, I witnessed extremes of emotion – people celebrating, hugging, jumping onto one another in a way I’d not seen before, but also heart wrenching scenes of tears and loud wailing.

382 migrants- all Sub-Saharan Africans, the vast majority of who were from West Africa, were rescued by the Topaz Responder crew that day. Most slept throughout the afternoon, understandably exhausted by their ordeal, as the ship headed north towards Sicily to disembark the migrants.

I took a break from shooting and only carried on in the early evening, around an hour or so before sunset, when the quality of light is at its best. I was doing a series of interviews and portraits as the sunlight turned a deep orange, when suddenly, the light seemed to be moving across the migrants faces very rapidly and in a matter of seconds, the sun which had been on the port side was now to starboard. The ship had performed a very tight 180-degree turn, and was now heading south again, in the direction of Libya. Many migrants appeared confused, as was I. It was nothing to be too concerned about – orders had come down from Rome MRCC to remain in the area, as many more boats could be expected the following day. The migrants would be transferred to an Italian coast guard ship that already had some 500 on board and was heading for the Sicilian capital Palermo. Needing to get back to Malta, I opted to do the same, transferring to the coast guard ship that night around midnight to start a 24 hour journey home.

A video of the rescues can be viewed here.

I’m away from home and family, sitting in the TV room on the Topaz Responder, a migrant rescue ship that’s operated by the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) off the coast of Libya. Deteriorating weather means we’re unlikely to see any activity over the next couple of days. My daughter’s trying to call me on Skype and several other VOIPs to wish me a Happy Father’s Day, without much success so far. I’m thinking of my own dad of course, now long gone though it still feels like yesterday. But, being on a migrant rescue ship, I’m also finding myself thinking back to all the fathers I’ve photographed with their children as they make what can best be described as a biblical journey driven by unimaginable fear and desperation. I’m in awe of these people who’d risk their own lives to protect and seek a safer future for their children. Yes, in doing so, they’re also risking the children’s lives, and sometimes it does go terribly and tragically wrong, but who wouldn’t do the same if faced with the same situation? It just goes to show how desperate their situation is, and reduces to ridicule the notion some people have that these migrants are simply embarking on these journeys for economic reasons.

I’m partly inspired to do this post because of a similar feature I read last week in the Huffington Post (which also featured some of my work).

Having spent more than a decade closely documenting the plight of asylum seekers in the central Mediterranean, I leapt at the opportunity to cover the story in Greece, Macedonia, Serbia and Croatia for the Jesuit Refugee Service earlier this year.

A lifejacket floats on the surface of the water at the port of Mytilene on the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

Biting cold air envelopes the small army of NGO volunteers coming from all over Europe on the rocky foreshore, close to the airport outside Mytilene, on the Greek island of Lesbos.

The volunteers are on the frontline of the migration crisis in the Aegean, looking towards the mountains that line the western shore of Turkey. They are searching for a glimpse of yet another boat of asylum seekers, risking life and limb in search of a better, and safer, life.

It’s part of a well-established routine now. Every morning, before dawn, the volunteers gather with their vehicles at various spots along the eastern coast, waiting for the inevitable arrivals.

Reports come in that, in the past hour, four boats on their way to our approximate location have been intercepted by the Greek coast guard. They are now being towed to safety, after they appeared to be in danger of foundering because of overloading. Only one rubber dinghy is expected, spotted through high-powered binoculars.

As the boat reaches the shallows, several volunteers in wetsuits wade into the water and take hold of it from all sides, to ensure it remains stable and there is no last-minute capsizing with potentially disastrous consequences.

Volunteers approach a rubber dinghy packed with refugees and migrants as they arrive on a beach on the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A baby cries as refugees and migrants arrive on a raft on a beach on the the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A migrant carries his baby after arriving on a rubber dinghy packed with refugees and migrants on a beach on the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A volunteer carries a migrant baby wrapped with a thermal blanket as refugees and migrants arrive on a raft on a beach on the the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A migrant boy wrapped in a thermal blanket stands on the beach moments after the arrival of a rubber dinghy packed with refugees and migrants on the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A migrant girl is covered with a blanket moments after refugees and migrants arrived on a raft on a beach on the the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A migrant child eats a banana as hot drinks are distributed moments after the arrival of a rubber dinghy packed with refugees and migrants on a beach on the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

There are more volunteers to meet the boat than there are men, women and children on board the dinghy. Though no single NGO is in charge, things appear to be relatively well organised. Everyone seems to know what they have to do. People are lifted and helped over the side; other volunteers are waiting with blankets and dry socks for the children. Further up on the beach, where the vehicles are parked, other volunteers have set out tables with hot drinks and food. It’s all over quickly. Less than half an hour after hitting shore, all the new arrivals are on buses operated by the UNHCR on their way to a reception centre.

Iranian migrants make their way at a makeshift camp near the village of Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

The reception centre at Moria is off-limits to the media and most NGOs. Surrounded by high walls lined with barbed wire, it appears ominous. Alongside it, another camp has sprung up, run by a loose coalition of local and international organisations. Known as Afghan Hill, it consists of hundreds of tents on a muddy hillside. Usually, people would only stop there for a day or two while they recover the strength before catching a ferry to the Greek mainland. However, a strike by the ferry workers which has dragged on for days means the camp, like others on the island, is now packed to bursting point as the number of arrivals keeps steadily rising while no one is able to leave.

Migrants are seen at a makeshift camp near the village of Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos, January 29, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

Getting to the border

A migrant child carries blankets carries as refugees and migrants disembark from the passenger ferry Blue Star1 at the port of Piraeus, near Athens, Greece, January 31, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A migrant carries a baby on her shoulders after refugees and migrants arrived on the passenger ferry Blue Star1 at the port of Piraeus, near Athens, Greece, January 31, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

The first ferry to reach the mainland in several days at the end of the strike disgorged a mass of humanity in the port of Piraeus. Several hundred people, heavily laden with all manner of belongings they’d received in the camps, poured onto the jetty, to be met by yet another army of NGO personnel and people offering transportation into Athens or straight to the border with Macedonia. Victoria Square, a small public garden in a grubby neighbourhood in downtown Athens, has become synonymous with the migration crisis. Migrants have been flooding the square for several months as it is close to metro stations, and more importantly, a stone’s throw away from the departure point of the buses that make the nightly overland journey to the Greek-Macedonian border.

My colleague and I join them on the long and uncomfortable trip. For some reason that remains unclear to me, the driver opts to stay off highways, adding considerably to the travelling time. People’s stories remain the same – most are fleeing from Assad’s bombs, the Islamic State and the Taliban, and all dream of their final destination being Germany.

Migrants sleep on a bus transporting them overnight from Athens, Greece, to the village of Idomeni on the Greek-Macedonian border late January 31, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

Ten hours later, at the crack of dawn, the bus pulls into a parking lot next to a petrol station outside the village of Polikastro, some 24 kilometers from the border crossing at Idomeni. The air is thick with smoke from bonfires around which people are huddling, seeking refuge from the freezing temperatures. The place is full of tents and parked buses.

Within a couple of days, the area will become a temporary stopping point for over 80 buses and 6,000 tired and desperate people, after striking taxi drivers across the border in Macedonia block the railway tracks leading north. The bus pulls to a halt behind several others. The driver explains the bus won’t be able to go further for several days because of the closed border. He suggests everyone disembarks and makes their way to the tents as they will freeze on the bus. Many of my travelling companions get to their feet and step out. British aid workers immediately give them blankets to wrap themselves in.

From my seat, I watch a group of around 20 of them walking towards a row of mobile toilets set up on the edge of the car park. I think nothing of it. Suddenly, they all break into a sprint and disappear into the undergrowth on the periphery. They won’t find themselves back on tarmac for dozens of kilometres, as smugglers will keep them off the roads as they trek towards gaps in the still-porous border between Greece and Macedonia. These people were all so-called economic migrants, who knew they would get no further if they tried to cross at the established refugee border crossings.

Things are relatively calm at the now-infamous camp on the border at Idomeni. With the refugees being stopped at Polikastro, the numbers have dwindled. They continue to trickle towards Macedonia on foot, where, once across, they pass through the Vinojug Temporary Transit Centre outside the village of Gevgelija. The odd train is being allowed through the taxi drivers’ blockade.

Refugees and migrants wait for a train to continue their journey towards western Europe from the Macedonia-Greece border at the Vinojug Temporary Transit Centre outside the village of Gevgelija, Macedonia, February 1, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

Many of the migrants however opt to use the taxis and buses to head further north to the border with Serbia. There is a long walk from the migrant transit camp near the Macedonia-Serbia border. Trains stop in the camp itself and disembark all their passengers. Unless they require medical care, most tend not to hang around, but immediately set off on foot. Those who do hang back sometimes try to jump onto a freight train that would be passing through.

A migrant plays with a child as refugees and migrants wait to continue their journey towards western Europe from the Macedonia-Serbia border at a transit camp in the village of Presevo, Serbia, February 2, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

The footpath across the border to a small camp on the Serbian side is littered with abandoned belongings. Blankets and sleeping bags flutter in the wind across the desolate and muddy landscape. Migrants only stop there for registration, and then make their way into the transit camp at Presevo, where they wait for the next available train or bus to take them up to the camps in Sid and Adasevci near the Croatian border. Croatian officials working in tandem with the Serbs question each person boarding a train at Sid to cross into Croatia. Here, we see clear evidence of how countries on the refugee route are using dangerously arbitrary criteria to determine who may and may not cross their borders – refugees must come from the ‘right’ country of origin and name the ‘right’ country of destination when questioned at the borders. Those criteria change on a regular basis. More worryingly, there doesn’t appear to be any effort to listen to individuals to determine their protection needs.

A man looks out of a window as migrants and refugees wait to continue their journey to western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Adasevci, Serbia, February 11, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A child walks onto a bus as migrants and refugees wait to continue their journey to western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Adasevci, Serbia, February 11, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

At Slavonski Brod, Croatia’s sixth largest city, a large industrial zone has been converted into a transit camp. Several times a day, trains carrying around a thousand migrants stop in the camp, and once again, everyone disembarks. Men and women of all ages, as well as children, queue through a complex of tents to be registered. The wind and rain pick up. Before long, an intense gale is ripping through the camp, knocking down tents and flipping over a couple of containers. Under a large marquee tent in which NGOs distribute clothing, food and hot drinks to the migrants, people desperately try to hold down the parts of the canvas that are flapping insanely in the wind. They know that if this marquee – packed with several hundred people – collapses, there will be a lot of injuries. Luckily that doesn’t happen. Once the storm abates, Croatian soldiers immediately move into action to repair the damage and re-erect the smaller tents that bore the brunt of the wind’s fury.

Migrants and refugees wait to continue their train journey to western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Slavonski Brod, Croatia, February 9, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

Migrants and refugees wait to be registered by the authorities before continuing their train journey to western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Slavonski Brod, Croatia, February 10, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A police officer talks with migrant children as migrants and refugees are registered by the authorities before continuing their train journey to western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Slavonski Brod, Croatia, February 10, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

Children play with bubbles blown by volunteers as migrants and refugees are registered by the authorities before continuing their train journey to western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Slavonski Brod, Croatia, February 10, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A migrant carries her baby as she makes their way to a tent where aid is distributed as migrants and refugees wait to continue their train journey to western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Slavonski Brod, Croatia, February 10, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

Migrants run in the rain to make their way to a tent where aid is distributed as migrants and refugees wait to continue their train journey to western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Slavonski Brod, Croatia, February 10, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

The migrants are only in the camp long enough to register, pass through the NGO tent to try get whatever supplies they may need and then return to the train, which will take them onwards on their journey into central Europe.

A migrant looks through a train window as migrants and refugees wait for their train to depart to Slovenia on their journey into western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Slavonski Brod, Croatia, February 10, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

A migrant looks through a train window as migrants and refugees wait for their train to depart to Slovenia on their journey into western Europe at a refugee transit camp in Slavonski Brod, Croatia, February 10, 2016. Photo: Darrin Zammit Lupi

This report was written before the EU-Turkey agreement on the return of migrants to Turkey came into effect.

It’s been a fantastic 2015 as far as my photography and journalism has been – An unusually busy one racking up the air miles – promoting Isle Landers at the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, Visa Pour l’Image Festival of Photojournalism in Perpignan and the Ballarat International Photo Biennale in Ballarat, Australia; fascinating and eye-opening assignments in east and southern Africa and off the coast of Libya; training in Belfast and Luxembourg; a brilliant photography convention in London with some cool awards thrown in; publishing a second book of photography (more on that soon).

I’ve put together a short video containing some of my favourite photos taken over the past year, covering things like the Je Suis Charlie demonstrations in Malta, migration in the central Mediterranean, some of my work for NGOs in Africa, as well as plenty of daily assignments done in Malta. Enjoy.